Why Trump country is unfazed by the child separation crisis

People who are accustomed to cruelty, on the giving and receiving ends alike, are not very likely to find such a policy appalling

The bishop of Tucson, Franklin Graham, and Michelle Obama agree about very few things, but the inhumanity of President Trump's "zero tolerance" border policy is one of them. The New York Times and the New York Post, National Review, Jacobin, and The Federalist all agree that detaining parents and children separately is a crude practice that should be abandoned.

To find a defense of the administration you must journey beyond civilization into the jungles of the conservative internet. Here amid the febrile light and heat you will learn from the sleek leopards of the canopy and the hideously sluglike boa constrictors in the understory that Trump's policy is, in fact, based upon the soundest principles of Christian statecraft, according to which the laws of Caesar are there to be obeyed; that, actually, this was former President Obama's policy first, not Trump's; that the administration found itself with no choice thanks to an obscure court decision; that, honestly, folks, it isn't that bad, it's practically daycare or a cozy public elementary school (and think of all the money we're spending on it that could go to natural-born Americans living in poverty!); and that, after all, the phonies and frauds in the Fake News Media don't care about children and are cynically exploiting this situation in order to score points against our indefatigable flag-respecting commander in chief.

You are also very likely to hear a defense of the policy from the average Trump supporter in the rural Midwest. Here in the bowels of Trump country, when the administration eventually reverses course, upsetting only Ann Coulter and a handful of contributors to Conservative Review, the images of sobbing children in metal boxes will have cost the president nothing. There are any number of reasons for this, many of which have to do with the ability of many voters to pretend that one or more of the non-arguments proffered above is convincing. But there are other, more important, reasons for this that are mostly invisible to members of my profession.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

One is that in many parts of the country where Trump enjoys wide support, the invasiveness of Child Protective Services is a fact of life. Everyone here knows what it is like to see their children or grandchildren or their nephews and nieces taken away, frequently for nonsensical and capricious reasons. The women my wife sees enjoying weekly supervised visits with their children at the local public library in our small Michigan town live in childless homes because their toddler fell down once or because a member of their family was convicted of taking or selling drugs. Parenting is something they have learned to conceive of as a kind of privilege rather than as a right.

They are accustomed to other sorts of random cruelties as well. Many of them live every day with the harassment of police officers, the condescension of teachers and social workers and the rest of the educational and public health bureaucracy, the leers of judges, the scolding of doctors and nurses, the incompetence of Veterans Affairs, even the smirks of grocery store clerks who seem to think that a woman who buys a case of beer while her children are in the shopping cart or when she is using food stamps to purchase her other groceries belong to a lower order of mammals.

Their manners have been barbarized almost beyond description. Just the other day I was walking next to my older daughter, who is 2 and a half, while she rode her tricycle. Eventually we came to a crosswalk and waited for the signal; when it appeared a pick-up truck that had missed the light came within two feet of hitting us. When I looked up at the driver he rolled down his window screamed, "Next time I'll just run your f--kin' kid over!" (He declined my invitation to pull over and further discuss the matter with me on the sidewalk.) Incidents like this are a wholly unremarkable feature of life in a world in which even the casual inconvenience of having to wait five seconds at a stoplight can give rise to quasi-homocidal rage and the ludicrous sense of power that comes from being behind the wheel of an automobile when there are pedestrians present is intoxicating.

How did this happen? It is almost impossible to give a succinct account, but any meaningful answer would involve the endlessly disruptive pace of modern life, the rise of the internet, the decline of religion, the disappearance of meaningful work, drug and alcohol abuse, and the resilience of atavistically crude manners.

None of this should be taken to suggest that the people I am talking about — even the one who almost ran over my daughter — are especially wicked. Anyone with a shred of empathy can see where most of these things come from. But there is a mode of politics in this country that appeals to the brokenness of their lives, the fracturing and poisoning of their imaginations, one that involves an affirmation of the thuggishness and despair with which they are so familiar and a suggestion that these feelings are the basis upon which a society might be organized. It did not begin with the rise of Trump. One could argue that it goes back to opposition to the civil rights movement or to the Know-Nothings or the anti-Federalists, all the way back to Cain and Abel, but I think in its modern incarnation it came into being with the Tea Party.

This was a movement that summoned out the inchoate rage of white Americans who had been left behind by free trade, the technologization of the economy, and the failure of Bushism to deliver at home or abroad, and found as its scapegoat a moderate neoliberal Democrat whose sole lasting achievement was the passage of the Heritage Foundation's health-care plan. The Affordable Care Act brought many of these people health coverage via the expansion of Medicaid. They do not know this. They only know that a man on television hated them for eight years. Now there is a different man on television who, if he does not love them, at least affords them a bizarre sort of respect. Above all he does not speak to them in the nauseating language of feel-good liberalism, except when it comes to the flag and the troops, the two universally agreed-upon objects of sentimentality. He speaks their own language of omnidirectional hostility and resentment.

President Trump's attempt to deter parents from immigrating by holding their children hostage is not going to lose him support among vast swathes of his base for the very simple reason that people who are accustomed to cruelty, on the giving and receiving ends alike, are not very likely to find such a policy appalling. They are wrong to feel this way. Their views are in fact — to use the D word — deplorable. But somehow I think that my anger and that of others is the last thing that is going to help them.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

UAW scores historic win in South at VW plant

UAW scores historic win in South at VW plantSpeed Read Volkswagen workers in Tennessee have voted to join the United Auto Workers union

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

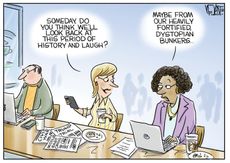

Today's political cartoons - April 22, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 22, 2024Cartoons Monday's cartoons - dystopian laughs, WNBA salaries, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Ukraine cheers House approval of military aid

Ukraine cheers House approval of military aidSpeed Read Following a lengthy struggle, the House has approved $95 billion in aid for Ukraine and Israel

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion ban

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion banSpeed Read The law makes all abortions illegal in the state except to save the mother's life

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

Trump, billions richer, is selling Bibles

Trump, billions richer, is selling BiblesSpeed Read The former president is hawking a $60 "God Bless the USA Bible"

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitness

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitnessIn Depth Some critics argue Biden is too old to run again. Does the argument have merit?

By Grayson Quay Published

-

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?Today's Big Question Re-election of Republican frontrunner could threaten UK security, warns former head of secret service

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By The Week UK Published

-

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?Talking Point Top US diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize winner remembered as both foreign policy genius and war criminal

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Last updated

-

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'Why everyone's talking about Would-be president's sinister language is backed by an incendiary policy agenda, say commentators

By The Week UK Published

-

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?Today's Big Question Republican's re-election would be a 'nightmare' scenario for Europe, Ukraine and the West

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published