Who will rise in the post-liberal world order?

In much of the West, anti-establishment energies appear to be taking ideologically heterogeneous form

From the voting booths of Brazil, where the far-right Jair Bolsonaro was recently elected, to the boulevards of Paris, where throngs of protesters smashed windows, overturned cars, and set fires this past weekend, fury against the parties, politicians, and ideas that have reigned supreme for the past generation is spreading across the Western world and gathering intensity along the way.

The target of this ire is "the establishment" — and the establishment is, broadly speaking, liberal. It favors the free movement of money and people, and believes these policies will generate economic growth sufficient both to give people hope for the future and to pay for social services generous enough to help those struggling to keep up. That was the deal: Elect liberals of the center-left or center-right, and they will manage the economy and the welfare state, technocratically tweaking it a little this way and that, raising or cutting taxes a little here and a little there, while for the most part getting out of the way so that the market can perform its magic, enriching us all over time.

It didn't work. In country after country, the policies embraced by the liberal establishment produced aggregate growth but benefits that were enjoyed only by some — namely, by the relatively well-educated residents of major cities and their surrounding suburbs, very much including the major cities where each country's political and economic elites live and work. Elsewhere, people have struggled to keep up or fallen badly behind.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In the U.S., suicide and drug addiction have become so common that life expectancy has fallen for the past three years. In Italy, the cost of living has so outstripped wages that young people can no longer afford to move out of their parents' homes, get married, and start families. In Spain, roughly one-third of those under the age of 25 are unemployed. And in France, the prospect of a modest increase in gasoline taxes has sparked waves of protest, with fed-up people venting anger and frustration at Emmanuel Macron, the country's arch-neoliberal president whose election just over 18 months ago was heralded by members of the international establishment as a victory of centrist good sense over the forces of illiberal reaction.

It's understandable that members of a liberal establishment under siege would respond to a potent challenge to its authority and privileges by portraying its antagonists as crazy, dangerous, or both. In many cases, the concern is fully justified. Bolsonaro, for example, has said some truly outrageous things and appears eager to embrace authoritarian modes of governance, just as Hungary's Viktor Orbán clearly wants to lead an international right-wing anti-liberal movement and has made a number of moves to put such ideas into effect at home.

But the fact remains that in many places the shape of anti-liberalism has yet to be determined. By portraying any dissent from the liberal consensus of the past generation as illegitimate and beyond the political pale, its defenders run the risk of driving its critics into the arms of demagogues, charlatans, and conspiracy nuts eager to empower themselves by taking advantage of the situation instead of helping to forge a new post-neoliberal politics.

Consider what's been happening in Germany. As in many countries throughout the West, the center-left party (the SPD) has gone into electoral freefall in recent years, while support for the center-right party of Chancellor Angela Merkel (the CDU) has also softened. One beneficiary of the implosion of the center has been a new far-right party, the AfD, which now sits in the German parliament and serves as the country's leading opposition party. Yet in recent months the left-wing Green party has benefitted even more, with its showing in recent regional elections and standing in national opinion polls revealing support exceeding both the SPD and AfD.

In Germany, anti-establishment energies appear to be taking ideologically heterogeneous form. The same is true in Italy, where the upstart Five Star Movement, which champions an ideologically eclectic range of positions, governs in a coalition with the right-wing nationalist League. The two parties are united primarily in their antipathy for the neoliberal consensus that prevails in the halls of the European Union bureaucracy in Brussels. That might send chills down liberal spines, but it shouldn't inspire dread in anyone else, since it promises a way forward somewhere between neo-fascism and the old pro-market center-right.

As Mark Lilla argues in an illuminating new essay paywalled in The New York Review of Books, something similar may also be happening in France, where Marion Maréchal-Le Pen (granddaughter of Jean-Marie Le Pen, founder of the far-right National Front, and niece of the party's president, Marine Le Pen) is working to foster a new political movement situated to the right of the center-right Republican party but separate and distinct from the extremism associated with her family.

This nascent movement is marked by a rejection of the individualism — or in American terms, the libertarianism — that characterizes so much of neoliberal thought. Like American conservatives, it valorizes traditional family structures, gender roles, and religion as a source of social cohesion and psychological meaning, while expressing hostility to multiculturalism and open immigration. But it combines these positions with skepticism of free markets and a genuine and deeply felt environmental ethic rooted in the conviction that the flourishing of human beings and the planet depends on reining in the dynamism of technological modernity and imposing a sense of limits.

There's little sign that the protesters wreaking havoc on the streets of French cities are motivated by social conservative convictions. Yet it's also true that their anger at the prospect of new gas taxes is accompanied by demands for a higher minimum wage, higher income taxes on the wealthy, a lower retirement age, a ban on outsourcing, and a maximum wage. Those could be planks in the platform of the party Marion Maréchal is working to build — or key elements in the next presidential campaign of Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the far-left provocateur who did surprisingly well in the first round of the 2017 presidential election, especially among young voters.

One thing is clear: None of it can be described as especially liberal. It makes sense for that to be an occasion for caution and concern. But it need not be a cause for panic and alarm.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

'Make legal immigration a more plausible option'

'Make legal immigration a more plausible option'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

LA-to-Las Vegas high-speed rail line breaks ground

LA-to-Las Vegas high-speed rail line breaks groundSpeed Read The railway will be ready as soon as 2028

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

Israel's military intelligence chief resigns

Israel's military intelligence chief resignsSpeed Read Maj. Gen. Aharon Haliva is the first leader to quit for failing to prevent the Hamas attack in October

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

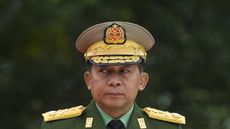

Myanmar: the Spring Revolution and the downfall of the generals

Myanmar: the Spring Revolution and the downfall of the generalsTalking Point An armed protest movement has swept across the country since the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi was overthrown in 2021

By The Week Staff Published

-

Israel hits Iran with retaliatory airstrike

Israel hits Iran with retaliatory airstrikeSpeed Read The attack comes after Iran's drone and missile barrage last weekend

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

Is there a peaceful way forward for Israel and Iran?

Is there a peaceful way forward for Israel and Iran?Today's Big Question Tehran has initially sought to downplay the latest Israeli missile strike on its territory

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Sudan on brink of collapse after a year of war

Sudan on brink of collapse after a year of warSpeed Read 18 million people face famine as the country continues its bloody downward spiral

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

How powerful is Iran?

How powerful is Iran?Today's big question Islamic republic is facing domestic dissent and 'economic peril' but has a vast military, dangerous allies and a nuclear threat

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

US, Israel brace for Iran retaliatory strikes

US, Israel brace for Iran retaliatory strikesSpeed Read An Iranian attack on Israel is believed to be imminent

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

How green onions could swing South Korea's election

How green onions could swing South Korea's electionThe Explainer Country's president has fallen foul of the oldest trick in the campaign book, not knowing the price of groceries

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Ukraine's battle to save Kharkiv from Putin's drones

Ukraine's battle to save Kharkiv from Putin's dronesThe Explainer Country's second-largest city has been under almost daily attacks since February amid claims Russia wants to make it uninhabitable

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published